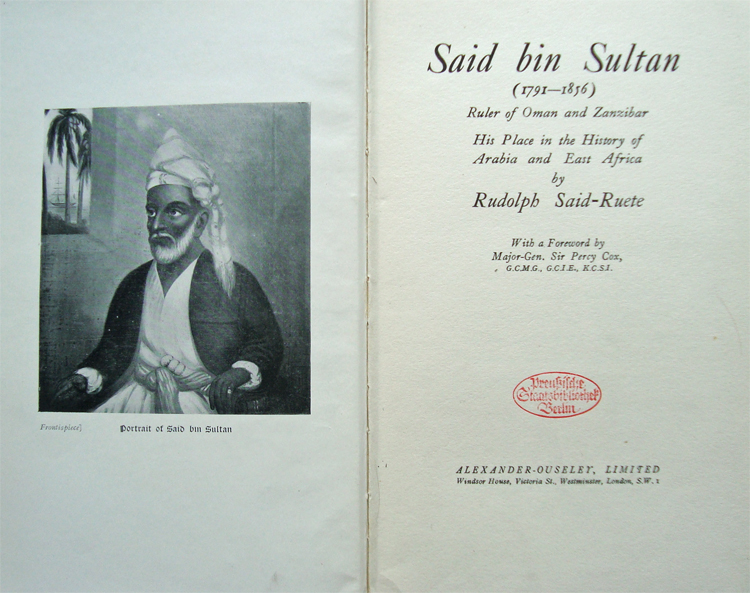

This book, written by his grandson, details the life and achievements of Emily Ruete’s father Sayyid Said bin Sultan. He became Sultan of Muscat and Oman in the early 19th century, and after 1845 the title “Sultan of Zanzibar” was added. During his ca. 50 years in power, he strengthened Omani control over the trade ports along the East African coast, moved the capital of his sultanate to Zanzibar, began political interaction with Europe and the United States, and transformed Zanzibar both into a world centre for the production of cloves and into the centre of the slave trade in the Indian Ocean.

Much loved by his daughter, Said bin Sultan plays an important role in her memoirs:

“Being one of the youngest of my father’s children I only ever saw him with his venerable snow-white beard. Above average height, he possessed in his countenance something exceptionally winning and benevolent, yet he commanded respect in every aspect of his appearance. […] He valued justice above all else and in the event of an offence there was no difference for him between his own son and a simple slave [...]” (Memoiren einer arabischen Prinzessin, vol. 1, p. 6).

Call number: Berlin State Library, Um 2544/10

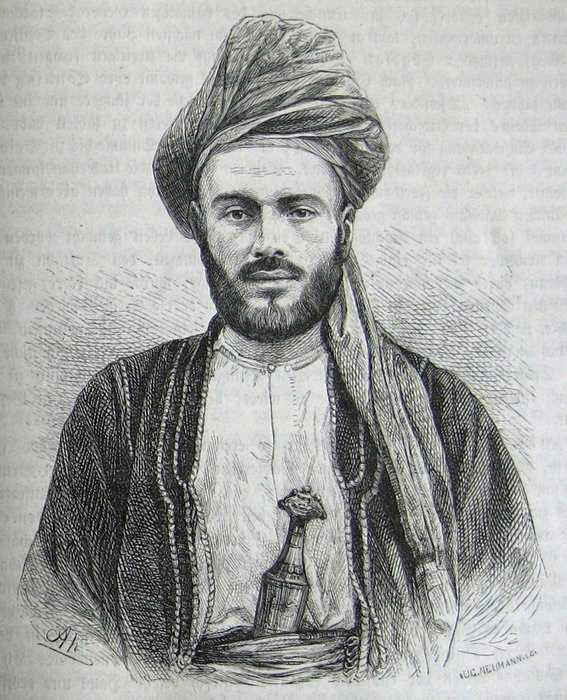

In: Otto Kersten, Baron Carl Claus von der Deckens Reisen in Ost-Afrika in den Jahren 1859 bis 1865: Die Insel Sansibar. Reisen nach dem Niassasee und dem Schneeberge Kilimandscharo [“Baron Carl Claus von der Decken’s Travels in East Africa in the Years 1859-1865: The Island of Zanzibar. Travels to Lake Nyasa and the Snow-Capped Mountain of Kilimanjaro“] (Leipzig/Heidelberg: Winter), 1869

“And yet Seid Madjid must have convinced himself of his sister’s guilt, for the princess was all of a sudden detained in her house and imprisoned. The poor girl sat here alone, abandoned, awaiting her sentence from a brother influenced by unbending tradition, never thinking help might come […]” (Baron Carl Claus von der Deckens Reisen in Ost-Afrika in den Jahren 1859 bis 1865, vol. 1, p. 114).

Madjid bin Said was Emily Ruete’s favourite brother. As Sultan at the time of his sister’s flight he played an important role – often one-dimensional and fairy tale-like – in narratives published before Ruete’s memoirs. In more recent retellings he is characterised variously as a weakling, a magnanimous pardoner, and as the stereotype of the older brother prepared to kill his sister to protect the family’s honour.

Emily Ruete was very close to her brother – he is an almost omnipresent figure in the childhood memories she narrates. Later she describes her guilt at not being punished by him for taking part in the palace revolution against his rule, led by Bargasch.

She also uses the example of her brother when taking issue with earlier narratives: “I never experienced any hostility from him on this account, let alone the imprisonment that has been the subject of some tall tales […] as a devout Muslim he believed in divine predestination and was convinced that this alone had taken me to Germany […]” (Memoiren einer arabischen Prinzessin, vol. 2, pp. 142 and 144).

Call number: Berlin State Library, 4° Us 935-1

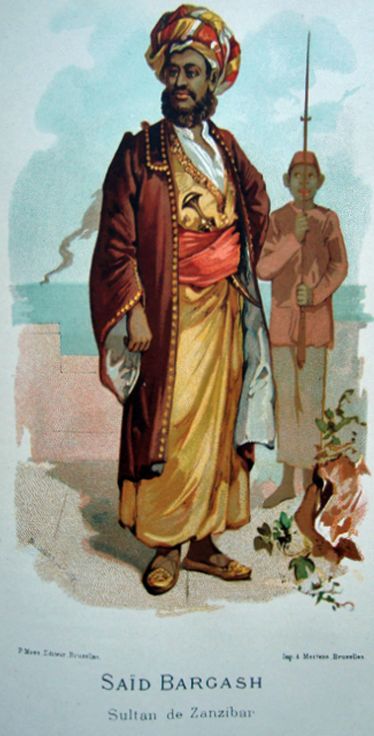

In this book by the Belgian explorer Adolphe Burdo the plate depicting Bargasch (Madjid’s successor as Sultan of Zanzibar) is inserted in the middle of his short but dramatic narration of the “love story” of Sayyida Salme and Heinrich Ruete: Burdo uses an overblown description of Bargasch’s seraglio as his entry point. Bargasch, described by his sister as “exceptionally talented [,...] proud and imperious by nature” (Memoiren einer arabischen Prinzessin, vol. 2, p. 100), plays a major, often contested, role in three chapters of her memoirs: as the initiator of the palace revolution against Madjid that later causes Emily Ruete (a participant) social difficulties; as the Sultan who travels to London in 1875 and is sought out there by his sister, hoping for his assistance, but finding the path to him blocked by the British Government; and finally as the unrelenting Sultan of 1885, who refuses his sister an audience. In her “Postscript to my Memoirs”, penned after his death, Emily Ruete also briefly presents more positive memories – and reveals that Bargasch was said to be the first reader of the memoirs in Arabic translation:

“[My brother Bargasch’s former personal physician] told me that when my memoirs were published in 1886 and my brother Bargasch received word of this, he commanded him to translate them word for word. When I asked him if he had dared translate the chapter “Said [sic] Bargasch in London” he answered that he had had to do that too and that it was precisely this chapter that had interested Said Bargasch the most. The gentleman also assured me that my brother had even bestowed some praise on the memoirs. This surprised me greatly [...]” (“Nachtrag zu meinen Memoiren”, p. 17).

Call number: Berlin State Library, 4° Us 3938