Otto Kersten

Baron Carl Claus von der Deckens Reisen in Ost-Afrika in den Jahren 1859 bis 1865: Die Insel Sansibar. Reisen nach dem Niassasee und dem Schneeberge Kilimandscharo [“Baron Carl Claus von der Decken’s Travels in East Africa in the Years 1859-1865: The Island of Zanzibar. Travels to Lake Nyasa and the Snow-Capped Mountain of Kilimanjaro“] (Leipzig/Heidelberg: Winter), 1869

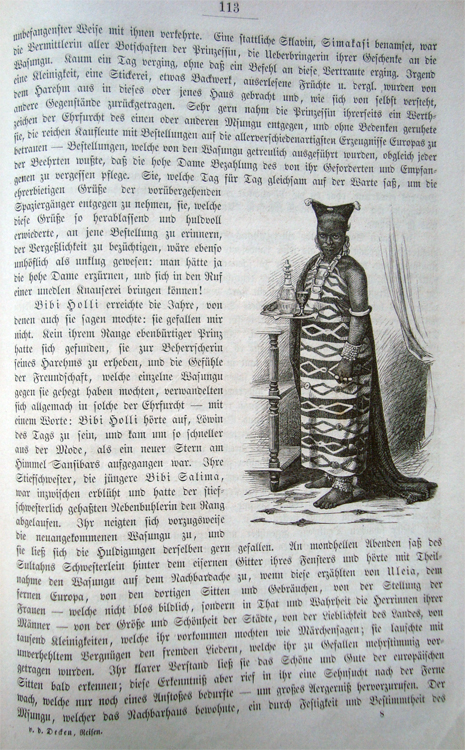

“Bibi Holli ceased to be the lioness of the day and went even more quickly out of fashion when a new star rose in the Zanzibar sky. Her stepsister, the younger Bibi Salima, had blossomed in the meantime and had surpassed her rival and the object of her stepsisterly hatred [...] On moonlit nights the sultan’s little sister sat behind the iron bars of her window and listened with interest to the Wasungu [Europeans] on the neighbouring roof […]” (Baron Carl Claus von der Deckens Reisen in Ost-Afrika in den Jahren 1859 bis 1865, vol. 1, p. 113).

The explorer Otto Kersten (1839-1900) had lived in Zanzibar for many years, and as a member of the von der Decken expedition, was instructed to publish a retrospective account of the journey. He added the “love story” of Heinrich and Emily Ruete into his discussion of Zanzibar. Through his title , “A Fairy Tale from the Thousand and One Nights Made Real”, and from the style of his narrative, he sets the tone for the later, fairy tale-like, orientalising narrations of this episode. He created many of the motifs copied by the later writers: Madjid’s imprisonment of the princess, for example, and the depiction of the sister “Holli” as a hated rival, both of which resonate with the actions of typical fairy tale characters – the Madjid and Chole of the memoirs were Emily Ruete’s closest siblings.

Call number: Berlin State Library, 4° Us 935-1

“Now an elegantly dressed couple came towards us. ‘Look at the lady closely’, whispered my friend. ‘Well now’, I asked, when the couple had passed, ‘what is special about her – she has a rather Southern complexion, probably an Italian or a Greek? –’

‘You’ve missed the mark, guess further south’

‘Perhaps even from India?’

‘Still further afield – she is an Arabian princess! Hear the story of how this lady of old Arabian princely blood became the happy wife of our compatriot. It is a story worth the telling – it sounds like a fairy tale from the Thousand and One Nights, it shows how love surmounts all bounds of nationality and, best of all, it is completely true down to the last detail’” (“Eine afrikanisch-europäische Liebesgeschichte”, p. 751).

This is an example of a version of Emily Ruete’s “love story” published before the memoirs. Its narrative style highlights a typical approach to this episode, fusing an orientalising fairy tale world, which could obviously be talked about “at the dinner table”, with claims to truth. This version appeared a year after Heinrich Ruete’s death. A subsequent letter to the magazine Daheim informs the readers of the tragic end to the “love story.”

Call number: Berlin State Library, 4° Ac 7250

“The sister of the current Sultan is introduced to us in the picture above, a picture which bears witness to the wonderful transformation of an Arabian princess into a respectable German lady. The story of how this transformation took place has been made the subject of romantic tales many times, but alas their embellishments, not always truthful, all too often fail to treat it with sensitivity, […] and we thus see it as our duty to report here once again, albeit briefly, on the facts, with the utmost truth” (“Die Schwester des Sultans von Zanzibar”, p. 444).

This article with its stylised image in which Emily Ruete has been rendered almost unrecognisable, functions as a description in the style of a Christian fable and shows just how hard the magazine is trying to tailor both her as a person and her story to contemporary societal expectations. Although some of what Emily Ruete says in the memoirs does tie in with this idea of an unproblematic “arrival” in German society – relativised in her later “Letters Home” – taken as a whole, the memoirs challenge the view implied in the magazine article, that an Arabian princess in and of herself cannot already be “respectable”, as well as its suggestion that Islam is “an obstacle to the development of the mind” (“Die Schwester des Sultans von Zanzibar”, p. 444).

Call number: Berlin State Library, 38 PC 225